👋 ASB Partners Nuggets 6.20.25

This is a short weekly email that covers a few things I’ve found interesting during the week.

Interesting Links/Reads

Many links are sourced from Marginal Revolution (bold and italics are my own to highlight what I found particularly interesting)

Even Better Russ Roberts Jun 15, 2025

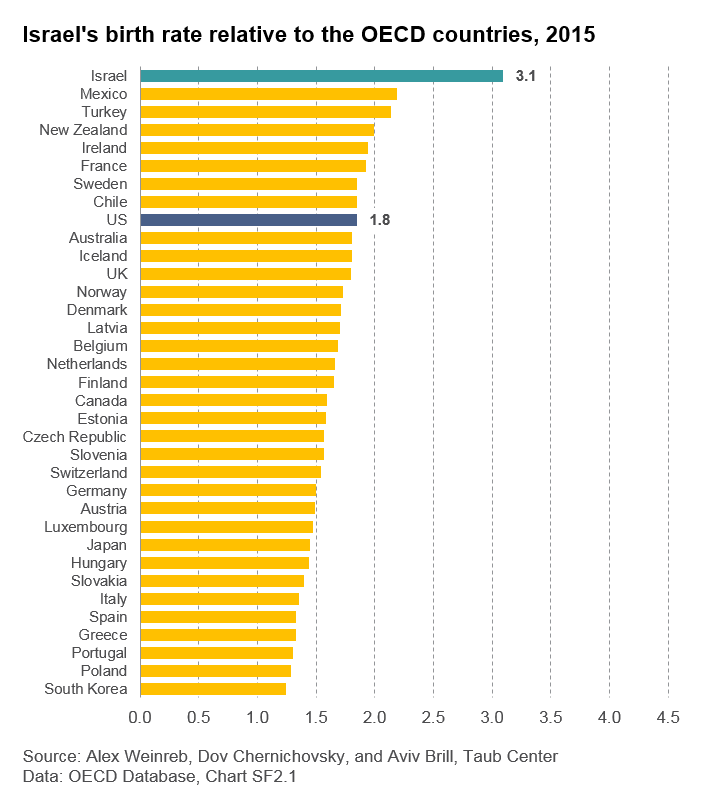

One measure of that optimism is family size. Israelis, religious and non-religious, have big families:

From the full report:

Another argument is that Israel’s high fertility is driven by certain parts of the population, such as Haredi (ultra-Orthodox) women, having many children (the fertility rate of Haredi women is indeed quite high at around 7 children per woman).

However, the rise in Israel’s fertility over the last two decades has been largely driven by the secular and traditional Jewish populations, whose combined fertility rate is greater than 2.2, which is itself higher than the overall fertility in any other OECD country.

But optimism is also part of everyday life here. On Thursday night before the attacks on Iran, we took some visitors from America to the shuk—the market called Machane Yehuda—the area of Jerusalem where bakeries and sellers of spices and fruit and vegetable merchants hawk their wares. At night, Machane Yehuda is mostly bars and restaurants blaring music. It’s a giant dance party and you will almost always see someone, sometimes not a young person, up on a table or chair dancing. This country loves life.

On Thursday night, at one of the crossroads of the shuk, there was pedestrian gridlock. There were maybe 75 young people, standing together, singing at the top of their lungs. Half of them were essentially blocking the intersection. The other half were standing on the equivalent of bleachers—ledges from closed storefronts at the intersection and available for getting above the street level of the people at foot level. A writhing mass of young people hands in the air swaying with the music that they were making, a capella. It looked like spring break in Florida. Everyone, except for the people who were trying to get by, was delirious with the happiness of the moment.

What were they singing?

They were singing Tamid Ohev Oti (He always loves me) a song that has become a handful of songs you hear over and over again these days. You will hear it in a restaurant on a Thursday night and because of the nature of the people who live here, people will start clapping along with the song and dancing, and yes, sometimes standing on chairs even in normal restaurants not in the shuk. This is a country that even in wartime (and this war with Iran is really not a few days old but 20 months old) is full of joy and exuberance. And you can find the song on social media—people singing it in the bomb shelters or stuck in tunnels waiting for the all-clear signal. People just start singing it because it captures something deep in the DNA of this country.

The “He” who always loves me in the song is God. Tamid Ohev Oti isn’t a romance song. It’s a religious anthem. The crowd screaming it out in the shuk was probably thinking more about the infectious beat than the meaning of the words. Because you don’t need to know Hebrew to enjoy the song. Crank it up:

Put aside the theology of the song that not everyone finds palatable. Just listen to the refrain: V’od yotair tov. It means “It’s going to get better.” Or “It will be better, still.” Or as good as life is now, it will be even better. Did the singers in the shuk really believe it as they belted it out? I like to think so. It’s an anthem of optimism in the middle of an ugly ugly war where all we do every day is wish each other b’sorot tovot, Hebrew for “May we hear good news.” One of the craziest things about this country is that we actually can imagine the arrival of good news. We almost expect it. We believe it’s going to get better. It may get worse before that happens. But ultimately, od yotair tov. Things will be better.

On June 7, Pope Leo XIV met with Argentine President Javier Milei at the Vatican. Mr. Milei reportedly gave the new pope a historical document from 1642, a handwoven vicuña poncho, and Austrian economist Friedrich Hayek’s 1988 book, “The Fatal Conceit: The Errors of Socialism.” Even though the book costs only $18.83 on Amazon, it was the most valuable gift.

Hayek’s fatal conceit is that “man is able to shape the world around him according to his wishes.” It’s a hearty defense of free markets—of classical liberalism. My colleague Matthew Hennessey got taken to task by the vice president for defending free markets on these pages. In 2025!

Hayek pounds home the point that markets are about price discovery. Wealth creation “is determined not by objective physical facts known to any one mind but by the separate, differing, information of millions, which is precipitated in prices that serve to guide further decisions.”

Catch that? By buying and selling in free markets to determine prices, you and I, and “millions who are connected only by signals resulting from long and infinitely ramified chains of trade,” drive the economy. We do it better than the self-selecting know-it-all-but-really-know-nothing blowhard intelligentsia.

Hayek rips these government meddlers: “The curious task of economics is to demonstrate to men how little they really know about what they imagine they can design.”

It isn’t that markets are anti-intelligence, it’s that they are best when run on their own, without interference, collecting all our price decisions. Natural collectivism, you might say, without anyone in charge. Markets know more. Did central planners tell engineers to invent microprocessors? No. Internet browsers? Netflix? GLP-1 drugs? Large language models? A thousand times no. Yet we have industrial policy mimicking Soviet five-year plans

At first, I wondered why Mr. Milei would give “The Fatal Conceit” to the pope, until I found this passage: “Man is not born wise, rational and good, but has to be taught to become so. It is not our intellect that created our morals; rather, human interactions governed by our morals make possible the growth of reason.” Righteous.

In the U.S. media, in books and documentary films, a different narrative prevails: Shareholder capitalism is at fault when planes crash but not when a million land safely. The interesting nuances of the second crash have gone almost unmentioned because it might seem somehow to let Boeing off the hook. We’ve seen a lot of this lately. Many reporters thought they were keeping Donald Trump out of the White House by not mentioning Joe Biden’s health problems.

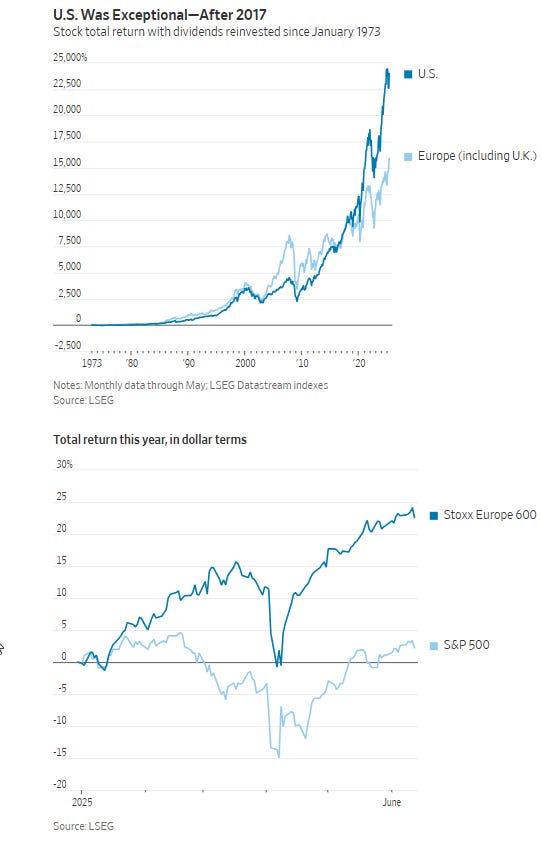

But too many people focus on the dismal returns since 2010, when the Greek crisis began, and forget that once Europe was a viable investment alternative. The scary stat: Since 2010 the S&P 500 is up more than 500%. European stocks are up less than 150%. The reminder: In the previous 15 years, from 1995, the S&P made only 130% while Europe gained 220%.

“There’s a rotation going on,” says Jim Caron, chief investment officer of the portfolio solutions group at Morgan Stanley Investment Management. “Europe’s got monetary policy stimulus, and it’s got fiscal policy stimulus. It has a currency tailwind.”

The trade-off confronting investors: The U.S.’s biggest stocks are more innovative and profitable but also far more expensive, while Europe’s are much less interesting but are cheap and have stimulus, plus an appeal to investors looking to diversify away from their highly concentrated U.S. holdings.

And now we come to the end game. Oh that Sinwar could see his patron, Iran, brought to its military knees in less than a week, Israel able to operate freely and destroy not just Iran’s military capability but to also pager-style, take out Iran’s military leadership and nuclear scientists.

. If I could whisper in his ear, I would whisper a single word: hubris. When you are riding high you are prone to think nothing bad can happen and that this winning streak is inevitable, deserved, and will continue indefinitely. That was Sinwar’s mistake on October 7. I hope Bibi knows that despite everything going his way for so long now, this moment is actually fraught with danger. As we move forward into uncharted waters with the future of Iran and the Middle East hanging in the balance, it would be wise to ask: and then what?

6.The Boss Can Spot a Bargain WSJ

Published as a book by H. Nejat Seyhun, “Investment Intelligence from Insider Trading,” it showed stocks with big insider buys and the lowest fifth of price-to-book ratios beat the market by a whopping 11 percentage points over a year.

The asset manager updated and expanded Seyhun’s observations and the results are even more compelling. First, it only counted large purchases—those exceeding $100,000—and just those by Csuite executives. It also looked at other developed countries. Then it applied a more complex measure of intrinsic value. Over a little more than

26 years ending in September 2022, Tweedy flagged 12,604 insider buys.

Dividing the results into 10 slices by value, from cheapest to most expensive, and using a longer time horizon, it found the cumulative excess return peaks after about two years. The cheapest decile beat the market by 25 percentage points while the most expensive lagged behind by 6 percentage points.

Podcast/Videos

COWEN: There’s a common impression — both for start-ups and for philanthropy — that doing much with K–12 education or preschool just hasn’t mattered that much or hasn’t succeeded that much. Do you agree or disagree?

ARNOLD: I agree. I think the ed reform movement has been, as a whole, a significant disappointment. I think there have been isolated pockets of excellence. It’s been very difficult to learn how to scale that. I think that’s largely true of many social programs or many programs that are delivered by people to people, that you can find a single site that works extraordinarily well because they have a fantastic leader, and that leader might be able to open up a few more sites. But then, when you start to scale it to 50 sites, and start to go across the nation, it all mean reverts back to what the whole system is providing.

That said, I do think there’s a lot of value in changing the incentives of the system and having the rewards and natural growth cycles and evolutionary components that are so strong and have been beneficial in the business world also go to the K–12 world. What I mean is that the service providers that are good and are delivering good results — both for parents and for kids — should grow faster than ones that aren’t. Right now, it’s kind of the same.

I think there’s a real question about whether government can be both the regulator and the service provider of the same program, which is what essentially independent school districts are today. I think the natural role of government is to be the regulator, and that they should be regulating third-party nonprofit providers. That model is what we support and has been rolling out across the nation. I think that the evidence is clear that it’s a better system, but it’s not delivering transformational results.

COWEN: Last two questions. First, what’s something you’ve learned about markets or society that you didn’t believe 10 years ago?

ARNOLD: I didn’t believe 10 years ago.

COWEN: You can make it 15, whatever.

ARNOLD: I think on society, it’s very hard to get people off of their baseline for the long term. There’re a lot of interventions that can happen that’ll change somebody’s short-term prospects, whether that’s a job training program or an addiction treatment program or an education program. You can bump them off that baseline for a little bit, and over time, there’s reversion to the mean. It’s made it very difficult to find social interventions that pass the benefit-cost test over the long term.

I think that’s why we were talking earlier about evaluations. We’re very focused on the evaluations that we fund, of trying to do long-term effects of programs and policies. Oftentimes, if you’re just looking at what the six-month effect is, you find an effect and a cost-benefit ratio that’s not relevant to what actual policymaking should be.

I hope you enjoyed it.

Adam